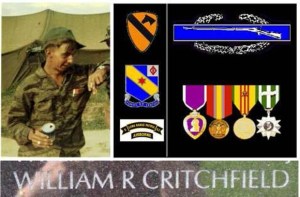

Specialist Four

E CO (LRRP), 52ND INFANTRY, 1ST CAV DIV, USARV

Army of the United States

Maple Shade, New Jersey

February 06, 1947 to December 27, 1967

Panel 32E Line 071

27th December 1967 1st Cav-Mission in the Suoi Ca Valley

I was 5 years old in May 1967 when my second cousin, William “Billy” Critchfield stopped by our house on a rainy New Jersey spring night to say goodbye to my family. He was heading out to Vietnam. He was wearing his dress uniform and shook my hand as he left. It would be the last time. It is one of my earlier memories, and it is as vivid as if it were yesterday.

1967 was a watershed year for the War in Vietnam. The number of US troops increased from 435,000 at the end of 1966, to 500,000 in 1967. Although public opinion regarding the war had been waning, Middle America and the media were tiring but still generally supportive of the war effort. By late 1967, after a series of border battles initiated by the PAVN (People’s Army of Vietnam) including Loc Ninh, Song Be, and Dak To, the war had reached a turning point and officers at MACV began to proclaim ‘light at the end of the tunnel’. US attrition objectives were being achieved: Vietcong and NVA units were apparently losing more forces in South Vietnam than could be replaced through recruitment or infiltration. Policy-makers in Hanoi also came to the conclusion that the war was stalemated and that battlefield trends were not in their favor. By December 1967, major operations throughout Vietnam had ceased and the war became a series of small unit clashes. Although it was generally not understood at the time, VC and NVA units were preparing for two major initiatives and moving men and material throughout the Central Highlands: The Siege at Khe Sanh would begin on the 21st of January 1968, and the Tet Offensive on Jan 30.

Billy Critchfield arrived in Vietnam on May 10, 1967 and was assigned to the 1st Cav. During the three-day in-processing, “cherries” (New replacements) typically received a briefing by the 1st Cav LRRPs. The “First Team” LRRPs had been established by Capt. Jim James in November 1966 and had been instrumental in providing long range reconnaissance throughout the 1st Cav’s wide-spread area of operations (AO) in the Central Highlands. After volunteering and completing the course, Bill was ultimately assigned to a First Team LRRP unit at LZ Uplift on Hwy 1 near the town of Bong Son with ~40-50 other LRRPs. Bill was well-liked and respected by team members.

LRRPs were a breed apart in nearly every way. They operated independently of the “regular” Army, with their own command structure reporting to G-2 Intelligence. They wore “tiger” fatigues similar to the South Vietnamese Rangers and Special Ops Studies and Observations Group (SOG). Steel pot helmets were exchanged for floppy bush hats. Their missions involved 5-6 man teams that were inserted into remote areas by helicopter at first light or nautical twilight. First light insertions were timed to execute the operation at “false dawn”, the brief transitional period of early morning as the darkness of night became a translucent grey just before the sunrise. Nautical twilight was the transitional evening period after sunset but just before the black darkness of night settled over the highlands. All LRRPs were volunteers – their missions were considered too dangerous for involuntary assignments. All LRRP volunteers had to pass a grueling 2-3 week training program where they learned a variety of skills including compass and map skills, radio, medical, tactics, and weapons training.

Missions would typically last 5-7 days often in areas of dense triple-canopy jungle, often outside the range of supporting artillery, or rapid reinforcement. Insertions were inherently dangerous and precise operations where a three hueys (known as a “slicks”), typically escorted by two

gunships, would approach the improvised landing zone (LZ) from a low-angle. The team would be on the first slick followed by the other two, running one after the other. The lead slick would pull close to the ground at a pre-selected LZ, often a small open saddle on a ridgeline. While the gunships lazily circled to provide support for incoming fire, the LRRP team would stand on the chopper’s skids as the slick pulled pitch into a momentarily stall and hovered 5-7 feet off the ground. The team, carrying ~100 lb packs each would jump to the ground. The other two ships would pass overhead and continue on and the team’s slick would fall into place as the third one in the line. The slicks and gunships would continue on, increasing elevation but remaining on-station to provide support in the event of ambush until the insertion team moved off of the LZ to a pre-established rally point 50-150 meters from the LZ.

The team would quickly “lay dog”, assembling in a wagon-wheel pattern, feet in the middle, squatting or lying prone with each LRRP dropping his pack in front of him both as protection and as a shooting platform. With 360 degree field of fire covered, the team would quietly wait, ensuring their insertion was undetected. Although the VC and NVA operating in the 1st Cav’s AO were initially caught unaware as the LRRP program spun up in ’66 and early ‘67, they quickly adapted their tactics. Special NVA Hunter-Killer tracking teams were soon operating throughout the highlands and sizeable bounties were offered to VC and locals alike for the killing or capture of LRRP teams. Although an insertion may have seemed successful, the teams had to worry first about VC or NVA units establishing an ambush, or discovering and overrunning them immediately after insertion. If that did not occur, the teams were concerned about being tracked and ambushed at anytime. The LRRP team members typically carried minimal firepower. M-16’s were traded-in for the shorter Car-15 carbines or an occasional Swedish K “grease gun” or other “exotic” weapons. LRRPs carried a double standard ammunition load of 18-20 20- round magazines. Without supporting artillery or immediate reinforcements, a 5-man team could be rapidly overwhelmed. The LRRP team’s best hope lay in remaining stealthy and ultimately undiscovered.

After intense observation for signs of attack or ambush, the team would load up and begin slowly moving through the jungle. They tended to avoid trails and would instead stick to covered areas where they could blend in with foliage. This often meant slow progress through “wait-a-minute” vines, thick bamboo forests, and triple-canopy undergrowth. The team would string out 8-10 meters apart with the most experienced team members taking turns “walking point” leading the team. The Team Leader (TL) would generally walk in the second position known as “Slack” and an experienced LRRP would bring up the rear, ensuring that all evidence of the team’s presence including bent branches and footprints were eliminated. Teams would occasionally circle-back on their route to determine if they were being tracked or followed. LRRPs moved silently, slowly, and deliberately observing and reporting any presence of enemy activity, trails, tunnels, weapons or food caches, as well as terrain features and foliage type. If the team detected sizeable enemy forces, they would radio in the position for artillery, air support, or helicopter gunships to decimate the enemy force while remaining hidden. On occasion, particularly later in the war, missions also included NVA/VC ambushes or prisoner-snatches.

LRRP teams would seek and establish positions of natural strategic or tactical advantage where observations could be made stealthily but could also be defended if attacked, and from which Escape and Evasion (E&E) could be conducted if the position was overrun. In establishing an observation point or a night position, the team would agree on the E&E plan as well as establish a perimeter 10-20 meters out and set trip-flares and, as night approached, claymore anti-personnel mines. They would also call in the periodic sitreps (Situation Report) and call in advanced firing coordinates in the event they needed artillery support.

On Dec 26, 1967, SP-4 Bill Critchfield returned from a mission with another team led by Bob Carr in a remote area in the Kim Son Valley in the Vinh Thanh Mountains known as the Crow’s Foot. He volunteered to join another mission scheduled for the next day. This mission was to be led by Sgt. “Montana” Joe Haverland. Bill was the Assistant Team Lead (ATL) joining Pat Blewett (RTO), Don Van Hook, and two South Vietnamese scouts Qui and Phi. The team lifted off from LZ Uplift the following morning for a first light insertion in the Suoi Ca Valley.

6 heading north near the mountains on the east side of the Suoi Ca Valley (South of AO) The Suoi Ca Valley lies ~20 miles south of Bong Son in the Binh Dinh Province and is named for the Suoi Ca stream that meanders through the craggy valley. The valley itself is approximately 20 kilometers long on a north/south axis that roughly parallels Highway 1, notoriously known since the French occupation as “La Rue Sans Joie” – The Street Without Joy , triangulated by Binh Khe to the west, Phu My to the northeast, and Phu Cat to the southwest. The insertion was successful and the team made their way to their first rendezvous point. After laying dog for 30 minutes or so, they began to reconnoiter the mountainside and deep ravines in the valley thick with triple canopy vegetation. The day wore on without excitement or significant discoveries.

6 heading north near the mountains on the east side of the Suoi Ca Valley (South of AO) The Suoi Ca Valley lies ~20 miles south of Bong Son in the Binh Dinh Province and is named for the Suoi Ca stream that meanders through the craggy valley. The valley itself is approximately 20 kilometers long on a north/south axis that roughly parallels Highway 1, notoriously known since the French occupation as “La Rue Sans Joie” – The Street Without Joy , triangulated by Binh Khe to the west, Phu My to the northeast, and Phu Cat to the southwest. The insertion was successful and the team made their way to their first rendezvous point. After laying dog for 30 minutes or so, they began to reconnoiter the mountainside and deep ravines in the valley thick with triple canopy vegetation. The day wore on without excitement or significant discoveries.

At approximately 5:00pm, the team located and established a night position on the side of a hill  Flight heading south over the Suoi Ca with the river visible and runway at Phu Cat Air Base near the center with a ~20 degree incline in an area surrounded by thick jungle with trees that afforded Montana the ability to climb a tree and view the valley floor. The team set out trip flares but held off setting out claymores. The VC and NVA were known to sneak up on positions and turn the claymores around on the team. Claymores would be deployed as night fell, often placing a pin released hand grenade under the claymore as a booby-trap if it were disturbed. The team settled in and began preparing dinner. On most missions, the team ate freeze dried LRRP rations – because standard C-rations were too heavy to pack in. On this mission, the team had also brought in the meat portions from some C-rations. As they started to prepare the meat, Phi and Qui went out into the jungle and brought back a number of plants and chopped them up and made a delicious stew that was heated using a small piece of C4 explosive lit on fire in a small hole in the ground. C4 burned hot and fast and was fairly smokeless and was often used to heat rations in the field.

Flight heading south over the Suoi Ca with the river visible and runway at Phu Cat Air Base near the center with a ~20 degree incline in an area surrounded by thick jungle with trees that afforded Montana the ability to climb a tree and view the valley floor. The team set out trip flares but held off setting out claymores. The VC and NVA were known to sneak up on positions and turn the claymores around on the team. Claymores would be deployed as night fell, often placing a pin released hand grenade under the claymore as a booby-trap if it were disturbed. The team settled in and began preparing dinner. On most missions, the team ate freeze dried LRRP rations – because standard C-rations were too heavy to pack in. On this mission, the team had also brought in the meat portions from some C-rations. As they started to prepare the meat, Phi and Qui went out into the jungle and brought back a number of plants and chopped them up and made a delicious stew that was heated using a small piece of C4 explosive lit on fire in a small hole in the ground. C4 burned hot and fast and was fairly smokeless and was often used to heat rations in the field.

At around 5:30, as the team was just getting ready to eat dinner, Montana whispered down to the team, “Gook.” A moment later, “Another one.” Several moments later he said “Shit. They’re all over the place.” An NVA anti-aircraft battalion consisting of 1,500 – 2,000 North Vietnamese Regulars were moving down the valley floor, hugging the edge of the tree line nearest the team’s position. As the RTO, Pat Blewett radioed in an artillery strike to decimate the large force.  As the artillery shells landed, Pat called in the coordinates, walking the artillery up the hill toward the team’s position. Normally, a force attempting to evade artillery shells would move in a different direction than where the shells were landing but for some reason, the main NVA force evaded directly up the hill on top of the team.

As the artillery shells landed, Pat called in the coordinates, walking the artillery up the hill toward the team’s position. Normally, a force attempting to evade artillery shells would move in a different direction than where the shells were landing but for some reason, the main NVA force evaded directly up the hill on top of the team.

Montana, still in the tree, called out “Let’s get the hell out of here.  ” The E&E plan called for the team to split up into two groups (Pat, Bill, and Phi) and (Montana, Van Hook, and Qui) and move in opposite directions around the hill and rendezvous in the valley on the other side. Bill and Phi were squatting on the ground in a defensive firing position to the left of Pat, packs on, ready to move. NVA soldiers simultaneously threw a satchel charge and sprayed the area with automatic weapon fire as it detonated. A satchel charge is a composed of high explosives packed into a canvas bag along with priming assemblies and a pull igniter and is typically significantly more powerful than a hand grenade. The charge landed several feet immediately in front of Bill and Phi. Pat had just pulled on his pack and was turning to say “Let’s move” when he saw a bright orange flash. He pulled the emergency release on his pack and kicked his legs out, landing prone on the ground as the satchel charge exploded.

” The E&E plan called for the team to split up into two groups (Pat, Bill, and Phi) and (Montana, Van Hook, and Qui) and move in opposite directions around the hill and rendezvous in the valley on the other side. Bill and Phi were squatting on the ground in a defensive firing position to the left of Pat, packs on, ready to move. NVA soldiers simultaneously threw a satchel charge and sprayed the area with automatic weapon fire as it detonated. A satchel charge is a composed of high explosives packed into a canvas bag along with priming assemblies and a pull igniter and is typically significantly more powerful than a hand grenade. The charge landed several feet immediately in front of Bill and Phi. Pat had just pulled on his pack and was turning to say “Let’s move” when he saw a bright orange flash. He pulled the emergency release on his pack and kicked his legs out, landing prone on the ground as the satchel charge exploded.

After the blast, Pat opened his eyes and looked to his left to discover Bill and Phi in a heap. The explosion blew a hole in Pat’s calf and shredded his backpack, which had not come off – likely saving his life. The explosion also blew off Qui’s heel and blew Montana completely out of the tree, injuring his back. Only Van Hook managed to escape serious injury. Pat and Van Hook immediately went to Bill and Phi who were unconscious and attempted to administer first-aid. LRRPs carried a med kit including cans of blood extenders (serum albumin). Unfortunately, the med kit had been in Pat’s backpack and was destroyed. Van Hook found a damaged can of albumin but sliced his hand open while attempting to open it. Meanwhile, NVA soldiers were still overrunning the position while evading artillery. As Van Hook helped Montana and Qui, into defensive firing positions, Pat radioed in the initial distress call with request for reinforcements and immediate evacuation.

After the blast, Pat opened his eyes and looked to his left to discover Bill and Phi in a heap. The explosion blew a hole in Pat’s calf and shredded his backpack, which had not come off – likely saving his life. The explosion also blew off Qui’s heel and blew Montana completely out of the tree, injuring his back. Only Van Hook managed to escape serious injury. Pat and Van Hook immediately went to Bill and Phi who were unconscious and attempted to administer first-aid. LRRPs carried a med kit including cans of blood extenders (serum albumin). Unfortunately, the med kit had been in Pat’s backpack and was destroyed. Van Hook found a damaged can of albumin but sliced his hand open while attempting to open it. Meanwhile, NVA soldiers were still overrunning the position while evading artillery. As Van Hook helped Montana and Qui, into defensive firing positions, Pat radioed in the initial distress call with request for reinforcements and immediate evacuation.

A 30-man recon team unit known as “The Blues” and “Red” team gunships from the 1st Squad/9th Cav were scrambled out of LZ Two-Bits near Bong Son. The 1/9 headed south into the mountains and valleys of the coastal plain toward Suoi Ca to insert the Blues platoon, secure the area, and extract the 1st Cav LRRP team. In a 2006 email to me, Paul Hart, the lead lift pilot described the following: “In the darkness of the mountains our gunships designated a landing zone (LZ) as close as possible to the team and we proceeded to air assault our Blues into the area. As we circled above the valley floor we could see our unit(s) in “contact” and tracers streaked through the air. During this “holding” period we had some airborne discussion regarding the extraction and medevac of the team, as well as our own Blues. “

The 1st Cav team had managed to set up defensive firing positions and in the darkness was working by sound only. In a recent email regarding the events of that night, Pat Blewett stated:

“Suddenly something set off one of our trip flares and Van Hook spun around to sweep the area on full-auto but I stopped him and got on the radio, ‘Blue, if you tripped that flare, tell me now.’ We received an affirmative reply. I answered back ‘You’re going across the mountain above us. I’m sending a man up to you. Don’t shoot.’ Van Hook went up to the Blues and we got everyone ready to go. Everyone, except Van Hook and I, were put on ponchos and carried out. Van Hook was able to walk on his own and I walked up the hill with two M-16’s for crutches and one on each shoulder. Van Hook and I dusted one gook hiding in some bushes on the way up.”

Paul Hart continued:

“I accepted responsibility for the extraction and medevac when we got the call. The other three lift birds would add the additional troopers that made up the squad I would leave behind. With the area still “hot”, [still shooting] we received a call from our Blues telling us that they had reached the LRRP team and needed immediate medevac. That was my call to go. I went into a makeshift LZ at the direction of our Blues and under cover of our guns. Obviously, at this point the adrenaline rush sets in and as a pilot you’re concentrating on the job at hand in this case it was landing in the dark, possibly under fire, getting the team on board, getting out of the LZ and to the nearest medical facility. In the few frantic and hurried minutes it took to land and load, I was able to glance around as the team was helped or placed aboard by our Blues. Some seemed to be conscious others not. My crew chief yelled “flights up” and we were gone. Fortunately, there was an aid station a short flight away. We were there and on the ground to waiting medical personnel within minutes. After everyone was unloaded we departed the area and returned to our base camp… As the Aircraft Commander (A/C) that evening, I was recommended for and received the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC). Something that I continue to display and take pride in — not because it came from an act of war, but more from an act of humanity – one soldier helping another – what more can be asked.”

Upon arrival at the med station at LZ Uplift, it was determined that both Bill and Phi had died from their injuries, most likely immediately. Both had multiple bullet wounds in the chest and extensive damage to the lower body from the satchel charge explosion. In all likelihood, neither Bill not Phi knew or felt anything before they died.  “Montana” Joe Haverland suffered back injuries and later returned to LZ Uplift for a few missions. He transferred to the 1/9 Blues until his return to the United States. Joe died in a car accident several years later when his car went off a cliff.

“Montana” Joe Haverland suffered back injuries and later returned to LZ Uplift for a few missions. He transferred to the 1/9 Blues until his return to the United States. Joe died in a car accident several years later when his car went off a cliff.

Pat Blewett spent several weeks in a hospital and returned to LZ Uplift to continue with the LRRPs. He received back injuries in a chopper crash during a mission in the A Shau Valley in 1968 and since he could no longer carry a backpack, he was reassigned to the 1st Cav’s 13 Signal Battalion where he worked until his eventual departure from Vietnam in January 1970. Pat grew up in Lodi, California, the sole surviving son of an Air America pilot who died in Vietnam in 1961. He joined the Army in 1967 at age 17. He is a retired long-haul truck driver and lives in Ione, California. Pat was essential in providing a first-hand account details regarding this fateful mission and did so without reservation.

Pat Blewett spent several weeks in a hospital and returned to LZ Uplift to continue with the LRRPs. He received back injuries in a chopper crash during a mission in the A Shau Valley in 1968 and since he could no longer carry a backpack, he was reassigned to the 1st Cav’s 13 Signal Battalion where he worked until his eventual departure from Vietnam in January 1970. Pat grew up in Lodi, California, the sole surviving son of an Air America pilot who died in Vietnam in 1961. He joined the Army in 1967 at age 17. He is a retired long-haul truck driver and lives in Ione, California. Pat was essential in providing a first-hand account details regarding this fateful mission and did so without reservation.

(http://www.tomah.com/lrrp_ranger/NamPhotos1/NamPhotos1.htm) In this photo, taken in 1968, Sgt. Bill Hand’s LRRPs, including Don Van Hook pose for a team photo at Camp Evans. Don Van Hook left Vietnam in November 1968. He died of cancer in North Carolina in the mid to late 90’s. For a description of his last mission, go here:

(http://www.tomah.com/lrrp_ranger/NamPhotos1/NamPhotos1.htm) In this photo, taken in 1968, Sgt. Bill Hand’s LRRPs, including Don Van Hook pose for a team photo at Camp Evans. Don Van Hook left Vietnam in November 1968. He died of cancer in North Carolina in the mid to late 90’s. For a description of his last mission, go here:

http://www.vietnamgear.com/article.aspx?art=44

Paul Hart was a Lift Pilot with the 1/9. He grew up in New Jersey and returned to become a police officer until his retirement several years ago. He now resides in Arizona. Paul once told me “I did a similar extraction within weeks of the 27th. Single ship, no Blues, guns for cover, coastal mountains, hot, dangerous and as exciting, but with better results. Everyone out, safe and home for another night. Couldn’t ask for more.” Interestingly enough, Pat Blewett was on that team as well. Paul has been “the man behind the scenes” since we first communicated in 2006. He has been an untiring ally reaching out to former First Team LRRPs, obtaining photos, and steering people like Bob Carr, Doc Gilchrist, Bill Carpenter, Earl McCann, Bill Hand, and Pat Blewett in my direction. It is ultimately from Paul, and through him, that this information came together. I am forever indebted for Paul’s assistance.

Paul Hart was a Lift Pilot with the 1/9. He grew up in New Jersey and returned to become a police officer until his retirement several years ago. He now resides in Arizona. Paul once told me “I did a similar extraction within weeks of the 27th. Single ship, no Blues, guns for cover, coastal mountains, hot, dangerous and as exciting, but with better results. Everyone out, safe and home for another night. Couldn’t ask for more.” Interestingly enough, Pat Blewett was on that team as well. Paul has been “the man behind the scenes” since we first communicated in 2006. He has been an untiring ally reaching out to former First Team LRRPs, obtaining photos, and steering people like Bob Carr, Doc Gilchrist, Bill Carpenter, Earl McCann, Bill Hand, and Pat Blewett in my direction. It is ultimately from Paul, and through him, that this information came together. I am forever indebted for Paul’s assistance.

Note:

This description of the Suoi Ca mission is a work-in-progress. I am always in search of information regarding missions in which Bill Critchfield participated, photos, stories, after-action reports, and other artifacts that help describe his service in Vietnam and his life. I can be reached at

deanl@cyberstrom.com

Dean Lindstrom

July 4, 2010

Ernie Daniels says: I was the Blue platoon leader inserted in this incident. We were saddled up to support a LRRP team under fire and inserted on a mountain top above the LRRP team. I don’t recall the exact time but it was at night and the LZ where we were inserted was barely large enough to hover. We had to be inserted one ship at the time and it was after the Red and White platoons had started their fire support. I don’t recall his name but we had just recently gotten a Red platoon leader and he was on site that night. After our insertion on the mountain top, we worked our way down the mountain to the LRRP site and as we approached ,we set off trip flares . I could hear the LRRPs trying to take us under fire but luckily, they were informed of our coming and didn’t shoot us up. Contact between the LRRP’s and the NVA had been broken by the time we got down to them but they were in pretty bad shape. As best as I can recall, there were five members of the LRRP Patrol. Of the 5, two were KIAs and the rest were WIAs. We got them back up to point of insertion and evaced them to the hospital at Quin Nhom.

Ernie Daniels says: I was the Blue platoon leader inserted in this incident. We were saddled up to support a LRRP team under fire and inserted on a mountain top above the LRRP team. I don’t recall the exact time but it was at night and the LZ where we were inserted was barely large enough to hover. We had to be inserted one ship at the time and it was after the Red and White platoons had started their fire support. I don’t recall his name but we had just recently gotten a Red platoon leader and he was on site that night. After our insertion on the mountain top, we worked our way down the mountain to the LRRP site and as we approached ,we set off trip flares . I could hear the LRRPs trying to take us under fire but luckily, they were informed of our coming and didn’t shoot us up. Contact between the LRRP’s and the NVA had been broken by the time we got down to them but they were in pretty bad shape. As best as I can recall, there were five members of the LRRP Patrol. Of the 5, two were KIAs and the rest were WIAs. We got them back up to point of insertion and evaced them to the hospital at Quin Nhom.

As an old man;s memory gets fuzzy, I recall that night as one of the worst insertions and extractions of my time as Blue ( call sign of the Infantry Platoon Leader). The conditions of the LRRP and the Ruggedness of the terrain remains burned in my memory.

Mike Askew says: One evening in December of 1967 just after dark our Charley Troop CP received word that a LRRP Team was pinned down on the side of a mountain south of Two Bits. My helicopter was dispatched to the area to cover the LRRP as they tried to break contact with the enemy. Upon arriving at their Position, we could hear the LRRP leader screaming on the radio for help. As we circled the dark three-layer canopy below, we could hear and see hand grenades exploding while tracers were skipped randomly across the jungle floor. We couldn’t tell the difference between where the enemy was located and where our friendly recon patrol was located. The LRRP leader was screaming that they were being over run by the NVA and needed help immediately.

Mike Askew says: One evening in December of 1967 just after dark our Charley Troop CP received word that a LRRP Team was pinned down on the side of a mountain south of Two Bits. My helicopter was dispatched to the area to cover the LRRP as they tried to break contact with the enemy. Upon arriving at their Position, we could hear the LRRP leader screaming on the radio for help. As we circled the dark three-layer canopy below, we could hear and see hand grenades exploding while tracers were skipped randomly across the jungle floor. We couldn’t tell the difference between where the enemy was located and where our friendly recon patrol was located. The LRRP leader was screaming that they were being over run by the NVA and needed help immediately.again and a few tracers coming up toward our helicopter. I said a quick prayer, hoping that our machine-gun fire would not hit our own troops.

being inserted on the top of the mountain about 500 meters from the LRRP position. The platoon then began the long walk down the dark dangerous mountainside toward the ongoing fire fight. We continued to cover the area with our fire still not knowing for sure where our friendly troops were. It wasn’t long before the Blues leader called to inform us that he was in contact with the LRRP leader and they were moving up toward the extraction point.

robert critchfield

October 29, 2011

dean,

this is a good read, and i know it took a lot of effort to gather all this info.

thank you and all the guys who came home to tell it.

bills little brother bobby

robert critchfield

Norma Lindstrom Rowe

March 10, 2012

Dean: Thank you for taking the time to collect the information and write the story of Billy’s last mission. You did a good job–your story answers a lot of questions. I also want to say thank you to all of the guys who served over there who contributed their recollections.

Norma Lindstrom Rowe

Patrick Blewett

September 19, 2013

Pat Blewett—–I glad to have finally been able to speak to a member of Bill’s family.For years I wished that I could.Only regret is it was not his parents.rest in peace my friend, one day we will meet again.

Pat Avery

December 29, 2013

I was a team member with willie from June 67 to nov 67. I left the lrrp com in nob to door gun on a Huey .i have always felt guilty for Willie death for leaving the team.maby he would not have gone on that mission if I would not have left our team. John Barnes was our TL with Bert Perconis and Willie and me pat Avery. This is the first time I have heard the whole story about that day. I hope God is taking care of Wiie

patrickbieneman

December 29, 2013

Pat, you can not blame yourself. Willie probably would have gone on that mission even if you were there. We do not control when our time is up. Just remember that YOU must live your life to the fullest because that is the only way that Willie’s death will be honored.

Brandon Kahlich

February 27, 2014

Very well written. I was told my uncle was part of a LRRP team but both he and his wife passed years ago so I never found out for sure…regardless of whether he was or was not, I salute those that risked so much for their country, every soldier that has served on behalf of the USA truly deserves our respect for their time serving.

Christopher Martin

March 2, 2015

thank you for this story, and thanks to each and every soldier/flier involved… i was just a toddler when this was going on.. thanks to all for your service.

Dean

March 3, 2015

Patrick – Thank you for posting this story on your blogsite. I was not aware it was posted here and only saw the contributions by Mike Askew and Ernie Daniels and comments just now. Thank you, all.

patrickbieneman

March 3, 2015

Dean, I am sorry. I thought that I had asked your permission before I posted it.

Dean

March 3, 2015

Absolutely no need to apologize. You may have and I certainly would have agreed!

lamont watson

October 21, 2018

as a 173rd provisional LRRP in the Dakto highlands of 1967 including hills 1338 and 875, I know how the memories continue to mess with you. Peace be with you all. lamont

drobinbarker

March 19, 2019

I just found this outstanding writing on the Internet, dated July 4, 2010. I have an inquiry I do hope someone can assist me with.When I was in Marines’ boot camp, at Parris Island, SC, beginning in August 1972, one of my buddies was a Army veteran named Melvin Cooley. I recall he was from North Carolina possibly. Melvin was white, and stood about 5′ 7″ but not more.Melvin told me and one other, on the very rare occasions one could whisper, he was in a Recondo unit in Vietnam. Later, at our Platoon 286’s ‘Command Inspection’ and days later at final graduation as Marines on 6 November 1972, Melvin wore his Army ribbons. He had the Silver Star medal on his rack.He told me that on one of many missions, when his unit was hit by enemy fire, he personally dragged his fallen CO, a Colonel or light Col. I think, back from danger and received the SS for that action; preventing the enemy from taking the wounded officer into captivity or worse.Melvin had scars on the face from a mouth / face combat wound also.I lost track of Cooley c.1973; and never found his SS Citation on the Internet to date. He told me of his “Recon” training where he and others each had to kill a fleeing pig with their bare hands as one test of abilities, etc.Can you please let me know if there is a way of finding out about his Recondo schooling / unit, so I can track his service? I am so interested in it to this day.Our Senior Drill Instructor, who is my friend now and is also here in Florida, shares my interest. They used to shoot the shit in the DI’s house late at night. It was about VN of course. I was in the first rack outside the hatch of the house, as my last name began with a B.Thank you sirs. Yours faithfully, Robin (Veteran SSGT / E-6, USMC)Mr. D. Robin Barker – Port Saint Lucie, Florida

patrickbieneman

March 19, 2019

Check with the 75th Ranger Battalion they should be able to let you know.

drobinbarker

March 19, 2019

Thank you very much sir!

Pat Avery

August 7, 2022

I was on a team with Willie before this happened rest in piece my buddy

Pat Avery

July 18, 2023

I was a team member of Willies. I left the unit 2 weeks before it happened. God Bless you Willie

Charie carvey

March 17, 2025

thank you for providing the tales of the past. My father, Joe Montana Haverlandt, died much too early. He has left a legacy within his Children and grandchildren. You have provided the opportunity for his grandchildren to be proud of the soldier, his sacrifices, and his honor. Thank you.